Taming Infinity

This is the third post in a series on ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ (Akshara-Mantapa), my Kannada implementation of Borges’ Library of Babel. We’ve covered the “why” and the “what.” Now comes the “how”: the mathematics that makes infinity navigable.

The Series:

೧. The Dream of Ananta: why infinity, why Kannada

೨. Exploring the Infinite Libraries: a hands-on guide to both libraries

೩. Taming Infinity: You are here

೪. Engineering Infinity: Rust, WASM, and making it run

೫. Reflections from Infinity: what I learned

I. Previously

We played with two libraries. We saw that Basile’s Library of Babel maps every possible 3,200-character English text to a unique address, and that my ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ does the same for 400-character Kannada texts. We also saw that Kannada’s 57,324 grapheme clusters make everything more complicated than English’s tidy 29 symbols.

But I didn’t explain how any of this works. How do you make infinity searchable? How do you guarantee that every address leads to exactly one page, and every page has exactly one address? How do you compute this on the fly, without storing anything?

This post is the answer. Buckle up, it’s going to be a long one.1

II. Basile’s Algorithm (And What I Could Understand)

When I first decided to build this, I went looking for Basile’s source code or a detailed technical explanation. I was delighted to find various blogs and discussions trying to decipher how it works. The simplest explanation came from Vsauce:

- Each page is given a unique sequential page number in base-10

- An “algorithm” uses this page number as a seed to generate a unique big number

- That output is converted into base-29, so all letters + punctuation can be represented

- Invertibility comes from the fact that any English text can be converted to base-29, from which you can derive the seed, and hence the address

Keep track of this “big integer” point. I’ve used almost the same logic for my computation.

There’s a theory page on his site that gives the conceptual shape, and a GitHub repo that documents the seed generation algorithm. It uses some number-theoretic machinery that I won’t bore you with here. I couldn’t implement his exact approach, but I understood enough to solve the problem my own way. For the technically curious, I’ve written a separate technical document covering the full architectural details of my bijection engine.

So I did what any reasonable person would do: I went down a rabbit hole of academic papers, cryptography blogs, and late-night whiteboard sessions.

III. What I Needed

Before diving into solutions, I had to clarify what I actually needed. Three requirements:

1. Invertibility

The mapping between content and address must work both ways. Given any page content, I can compute its unique address. Given any address, I can compute its unique content. No collisions, no gaps, no ambiguity. This is the core promise of the library: everything exists, and everything is findable.

2. Non-boring Adjacency

If page 1000 contains “ಕನ್ನಡ ನನ್ನ ಮಾತೃಭಾಷೆ” (Kannada is my mother tongue), page 1001 shouldn’t contain “ಕನ್ನಡ ನನ್ನ ಮಾತೃಭಾಷೆ “ (the same thing with one extra space). Adjacent addresses should feel random, unrelated. The scrambling should be thorough.

Why? Because otherwise browsing becomes predictable. You’d see patterns. The infinity would feel… finite. And also, unlike an actual library where things are ordered by systems, this is for fun. This is also how Basile did it, and I’ll link you to his reasoning on it.

3. Computationally Cheap

This has to run in a browser. No server round-trips for basic operations. The user clicks “random page” and gets a result instantly. The math needs to be fast, even with enormous numbers.

IV. Engine Logics: An Open Challenge

Before settling on my approach, I explored several “engine logics”, different mathematical frameworks for mapping content to addresses. Each has tradeoffs. I’m listing them briefly here.

If any catches your interest, consider it an open challenge. Build a Kannada library (or Telugu, or Tamil, or Malayalam) with a different engine. I’d love to see it.2

| Engine Logic | Core Idea | Why I Didn’t Use It |

|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic coding bijection | Treat the text as a probability distribution, encode as a single number | Complex to implement invertibly; doesn’t naturally scramble adjacent pages |

| Space-filling curves (Hilbert, Z-order) | Map multi-dimensional space to a single line while preserving locality | Preserves locality, which is the opposite of what I want; adjacent inputs stay adjacent |

| Gray code addressing | Adjacent numbers differ by only one bit | Same problem: designed to preserve adjacency, not destroy it |

| Block ciphers (AES-based) | Encrypt content as if it were a message | Block size limitations; would need format-preserving encryption for arbitrary lengths |

| Permutation polynomials | Use polynomial functions over finite fields | Promising but complex; hard to guarantee bijectivity for non-prime moduli |

Each of these is a valid path. Someone smarter than me might make them work beautifully. I went with something simpler.

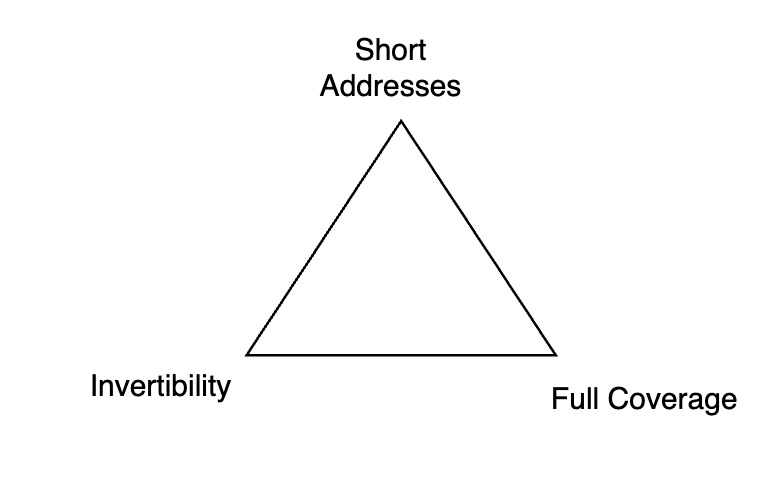

V. The Babel Trilemma

As I explored these options, a pattern emerged. I started calling it the Babel Trilemma3:

You can have at most two of three:

Short addresses: Human-readable, compact location strings. Something you could write on a napkin. (Or text to someone, for the gen-z folks 😛.)

Invertibility: Bidirectional mapping. Content → address and address → content, both computable.

Full coverage: Every possible text has exactly one location. No gaps, no duplicates.

Pick two.

-

If you want short addresses and full coverage, you lose invertibility. You’d need a lookup table the size of infinity. (And you’d be going up against the pigeonhole principle).

-

If you want short addresses and invertibility, you lose full coverage. You can only map a subset of possible texts.

-

If you want invertibility and full coverage, you lose short addresses. The address must encode enough information to reconstruct the content, which means it grows with the content space.

I chose invertibility and full coverage. I gave up short addresses. I wanted true infinity, not some make-believe browser-friendly version.

The result: my addresses are hexadecimal strings up to ~1,590 characters long. Not pretty. Not napkin-friendly. But mathematically sound.

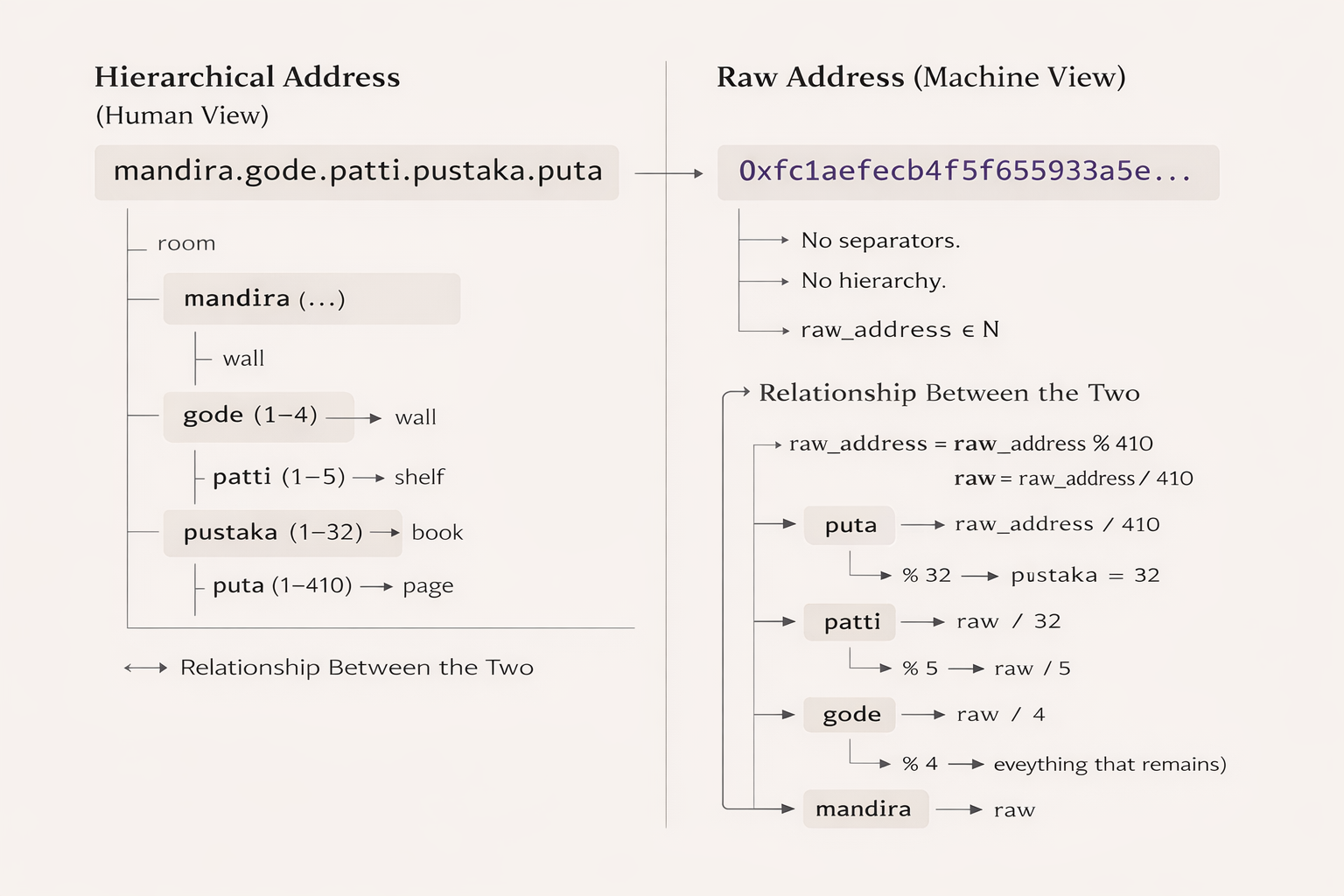

VI. The Address System: Hierarchical and Raw

Before diving into the math, let me explain how addresses actually work in ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ. I use two representations: hierarchical (for us pleb humans) and raw (for the backend).

Address Equivalence

The hierarchical address looks like mandira.gode.patti.pustaka.puta (room.wall.shelf.book.page). It’s readable, it maps to Borges’ vision, and it gives you a sense of location in the library.

But here’s the thing: most of the infinity lives in the mandira (room) component.

The mandira identifier alone can be around ~1,000 hexadecimal digits long, encoding the vast bulk of the address space. The wall, shelf, book, and page numbers are trivial by comparison, just small integers that subdivide each room.

The raw address is the full hexadecimal string, what the bijection engine actually operates on. When you search for text, the engine returns a raw address; the frontend then parses it into the hierarchical format for display. When you browse to a hierarchical address, it gets packed back into raw form for computation. Two views of the same underlying number, one for humans and one for math.

VII. The Modular Arithmetic Approach

Here’s what I actually built.

The Intuition

Imagine a clock with N hours, where N is incomprehensibly large (57,324^400, the number of possible Kannada pages).

Now pick a special number C that has no common factors with N (they’re “coprime”).

If you multiply any hour by C and wrap around the clock, you get a different hour. And here’s the magic: this mapping is reversible. There exists another number I (the “multiplicative inverse” of C) such that multiplying by I undoes the multiplication by C.

So:

- Start with content (as a number)

- Multiply by C, wrap around → address

- Multiply by I, wrap around → back to content

No information lost. It’s also super cheap to compute.

Simple example of how mod arithmetic works for indexing

The Formula

address = (content × C) mod N

content = (address × I) mod N

Where:

N = 57324^400(the total number of possible pages)C= a carefully chosen coprime multiplier4I = C⁻¹ mod N(the multiplicative inverse of C)

Finding the Inverse

How do you find I? The Extended Euclidean Algorithm. Given two coprime numbers C and N, it finds integers I and J such that:

C × I + N × J = 1

Rearranging: C × I = 1 (mod N)

So I is the multiplicative inverse of C. This algorithm is ancient, efficient, and beautiful. It runs in O(log N) time, which is crucial when N has thousands of digits.

The Scale

Here’s where it gets fun. N is approximately a 6,300-bit integer. That’s a number with roughly 1,900 decimal digits.

Standard 64-bit arithmetic won’t touch this. Even 128-bit won’t help. I needed arbitrary-precision integers, numbers that can grow as large as necessary.

In Rust, the num-bigint crate handles this. The multiplicative inverse gets computed once at startup (takes a fraction of a second), and then every page lookup is just one big multiplication and one modulo operation. Since N is fixed (number of graphemes isn’t changing) and C isn’t changing (keeping a fixed value), C and I are also fixed. Hence every time you run the same code, you’ll get the same results. Fast enough for real-time browsing.

Why This Scrambles Well

Remember requirement #2: adjacent pages shouldn’t look similar. Multiplication by a large coprime does this naturally.

If content A and content B differ by 1, their addresses differ by C (mod N). Since C is enormous and has no structure related to “meaningful text,” the addresses are scattered across the entire space.

It’s not cryptographically secure scrambling, but it doesn’t need to be. It just needs to feel random and it does.

VIII. A Worked Example

Let me show this with small numbers so you can see the mechanics.

Suppose:

- Alphabet size: 3 symbols (a, b, c)

- Page length: 2 characters

- Total pages: N = 3² = 9

- Coprime multiplier: C = 5

- Multiplicative inverse: I = 2 (because 5 × 2 = 10 = 1 mod 9)

Content “aa” = 0, “ab” = 1, “ac” = 2, “ba” = 3, etc.

| Content | As Number | × 5 mod 9 | Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| aa | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ab | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| ac | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| ba | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| bb | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| bc | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| ca | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| cb | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| cc | 8 | 4 | 4 |

Every content maps to a unique address. Every address maps to a unique content. And adjacent contents (0,1,2,3…) map to scattered addresses (0,5,1,6…).

Now scale this up to 57,324 symbols, 400 positions, and 6,300-bit integers. Same principle, just… bigger.

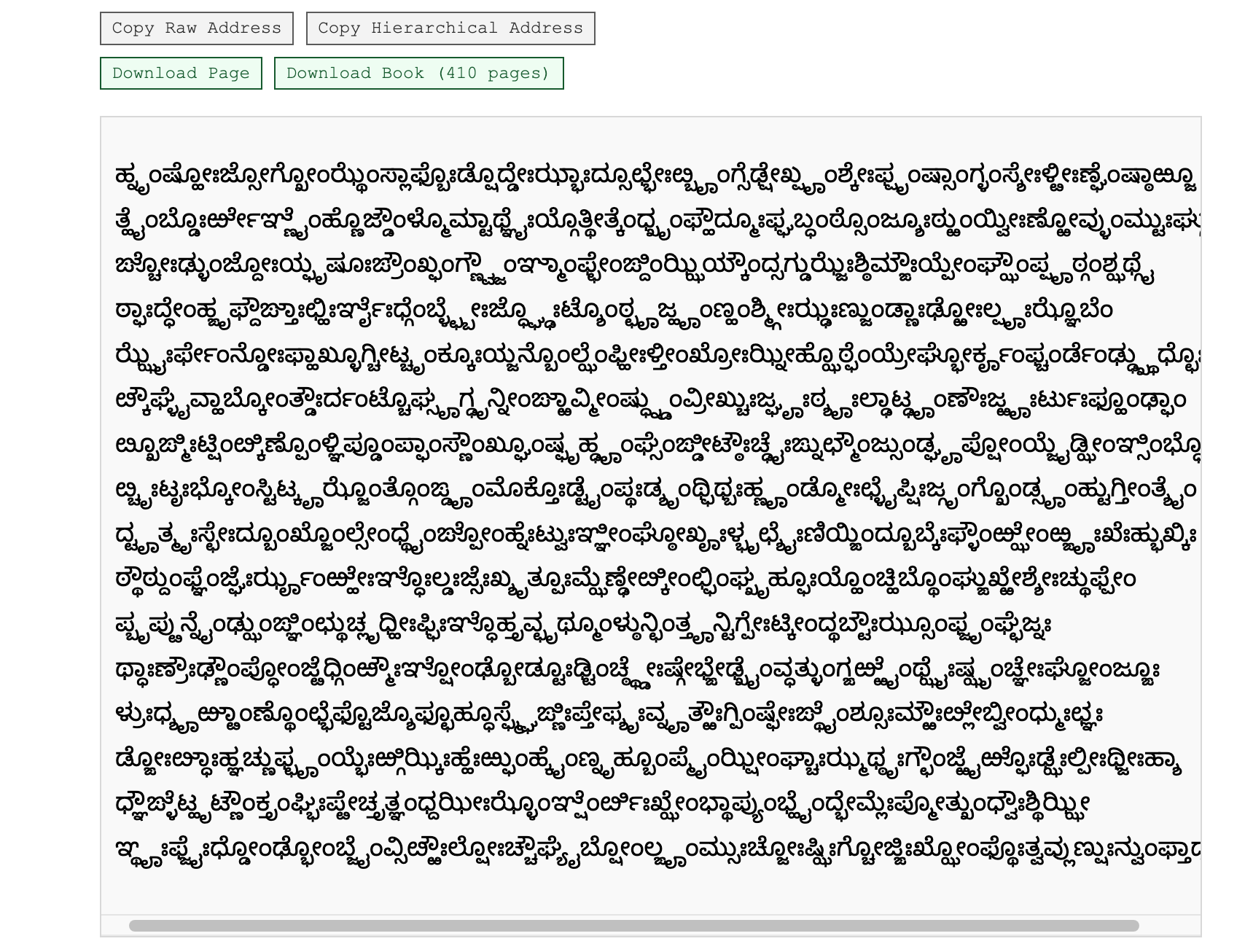

IX. The Wall of Text Problem

I should acknowledge a weakness in this approach, one shared by Basile’s library.

Most pages look like noise. Dense, unreadable walls of random grapheme clusters. This is mathematically correct: meaningful text is vanishingly rare in the space of all possible strings. If you browse randomly, you’ll never find anything readable. The probability is too small to comprehend.

Looks very… random?

Why This Happens: Zipf’s Law and Uniform Distribution

In natural Kannada text, grapheme clusters don’t appear with equal frequency. Some clusters like ಕ, ನ, ರ appear constantly, while others like ೞ or complex conjuncts are rare.

This follows Zipf’s law: a small number of clusters do most of the work, while the long tail of rare clusters appears infrequently.

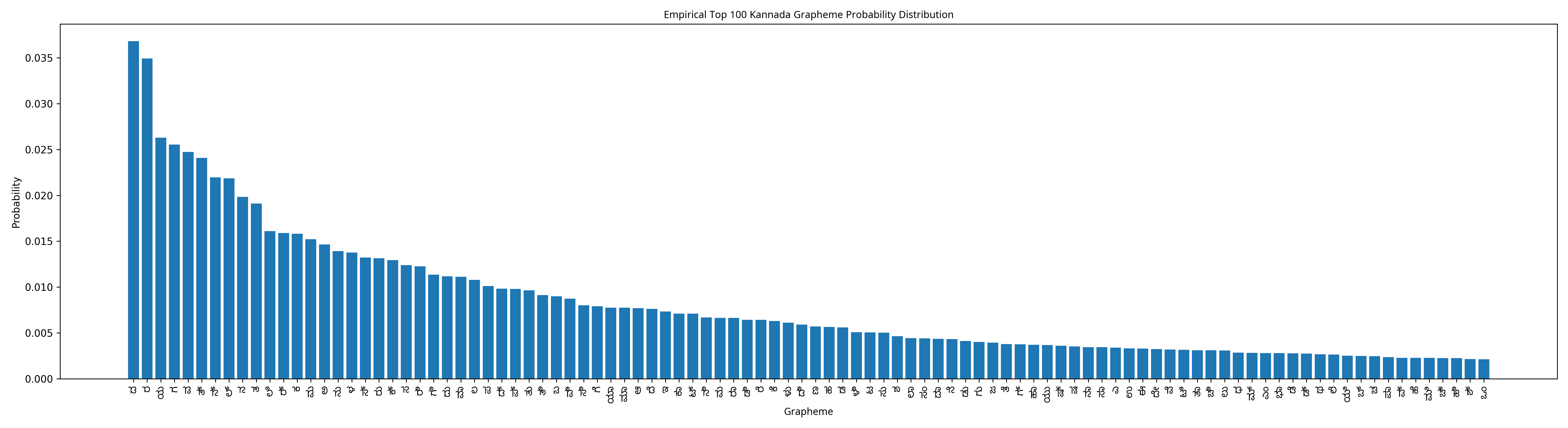

Generated plot from ಕನ್ನಡ wikipedia dump

Look at that curve. The most common grapheme has a probability of about 0.035 (3.5%), and it drops off steeply. The top 100 clusters account for most of natural Kannada text; the remaining 57,000+ clusters share the scraps.

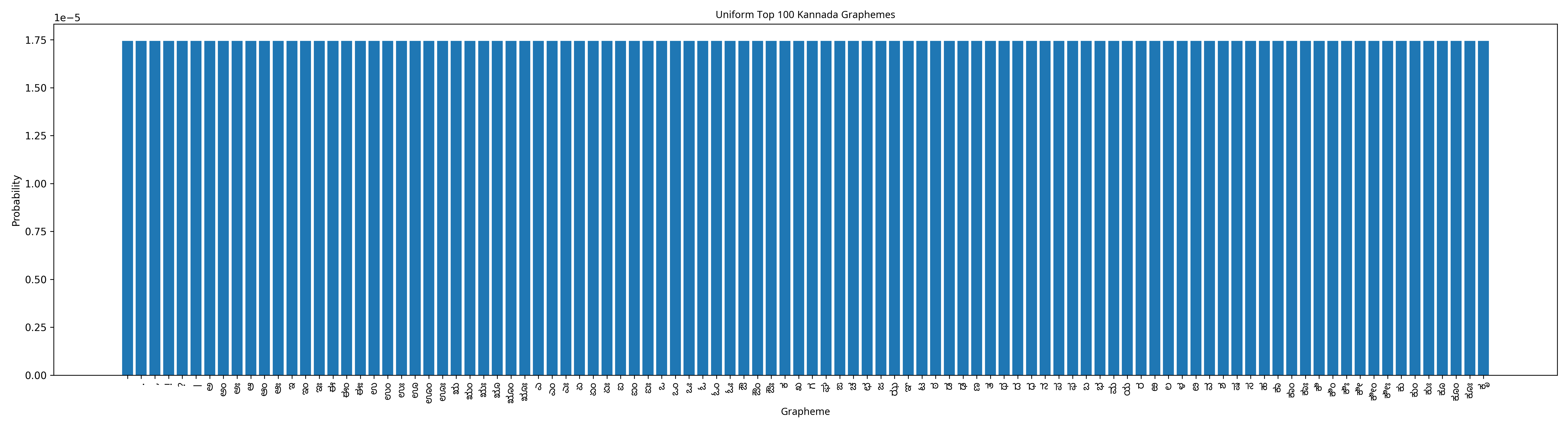

But in the library, every cluster has equal probability. The distribution is perfectly uniform:

Generated plot for uniform grapheme distribution. They’re not even in the same scale!

Notice the y-axis: 1e-5, or 0.00001. Every single grapheme, whether it’s the ubiquitous ಕ or some obscure conjunct you’ve never seen, has the same probability of roughly 1/57,324 ≈ 0.0000175. The most common cluster in natural text is about 2,000 times more likely than any cluster in the library’s uniform distribution.

This is the disparity that makes the library feel alien. In natural Kannada, you see familiar patterns because common clusters dominate. In the library, rare clusters appear as often as common ones, creating text that looks like Kannada script but reads like static. Your eyes recognize the shapes; your brain finds no meaning.

The library contains every Kannada poem ever written. But it also contains 57,324^400 pages of gibberish for every one page of meaning.Infinity doesn’t care to dress up.

But it does make the browsing experience… existentially bleak, sometimes.

A future version might explore weighted distributions, biasing toward more “language-like” outputs. But that would compromise the purity of true infinity. Every choice has tradeoffs. For now, I’ve kept it pure.

X. What’s Next

The math is solved. We have:

- A bijective mapping between content and addresses

- Efficient computation using modular arithmetic

- Arbitrary-precision integers to handle the scale

- Thorough scrambling so adjacent pages feel unrelated

But knowing the math and building a working system are different things. How do you structure the code? How do you make it run in a browser without a backend server? How do you handle the frontend, the UI, the deployment?

Next post: Engineering, where I talk about Rust, WebAssembly, SvelteKit, and the art of being too lazy to pay for hosting.

Next: Post 4 — Engineering Infinity

P.S. I suspect the only folks who will read this far are the ones trying to reverse-engineer the algorithm so they can build a Library of Babel for other languages. If that’s you, check out the full technical documentation and shoot me a mail. I’d love to hear about it.

-

I’m not an actual mathematician or cryptographer, and my approach might be heavily flawed. Do mail me with any changes or errors you might find, and I’ll gladly correct my approach. ↩

-

For any of you nerds, you need to start tinkering in the

alphabet.rsand then build on. (There’s surprisingly more changes that I thought, but I wanted to keep the implementation simple enough, not future proof to be extended to annthlanguage lol) ↩ -

I’m very sure that somewhere in some Information theory textbook, “the reader can see it’s obvious…” regarding this, but I’m too dumb for that lol. ↩

-

In the actual code, I start from

314159265358979323846264338327950288419and then find the coprime by just incrementing until I get one. Thank godBigUintin Rust can handle numbers this big! (I didn’t even read half the digits, I just picked it from our all-time favourite π!) ↩