Engineering Infinity

This is the fourth post in a series on ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ (Akshara-Mantapa), a Library of Babel for Kannada. With the philosophical motivation established and the mathematical framework in place, this post turns to the concrete structure of the project: the actual bones of the website and how they fit together.

The Series:

೧. The Dream of Ananta: why infinity, why Kannada

੨. Exploring the Infinite Libraries: a hands-on guide to both libraries

೩. Taming Infinity: the mathematics of bijection

೪. Engineering Infinity: You are here

೫. Reflections from Infinity: what I learned

I. Previously

We solved the hard problem. Bijective mapping between content and addresses, modular arithmetic with 6,300-bit integers, the Babel Trilemma and its tradeoffs. The math works on paper. The algorithm is sound (at least until someone cryptanalyses the shit out of it).

But an algorithm isn’t a product. Someone needs to type a URL into a browser and see infinite Kannada text. That’s a different kind of problem, and honestly, a kind I’m less comfortable with. I’m more at home with number theory than with CSS.

This post is about the engineering: how the code is structured, why I chose Rust, how I got it running in a browser without paying for servers, and where I leaned heavily on Claude to fill gaps in my knowledge. Consider it a guide for anyone who wants to fork this for another language.

II. Design Philosophy: ಭಾಷಾ-ಅಜ್ಞೇಯ (Language-Agnostic)

From the start, I wanted the architecture to be language-independent. Kannada was my target, but the same engine should work for Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, Devanagari, or any script with a definable set of grapheme clusters. ಭಾಷಾ-ಅಜ್ಞೇಯ: script-agnostic.

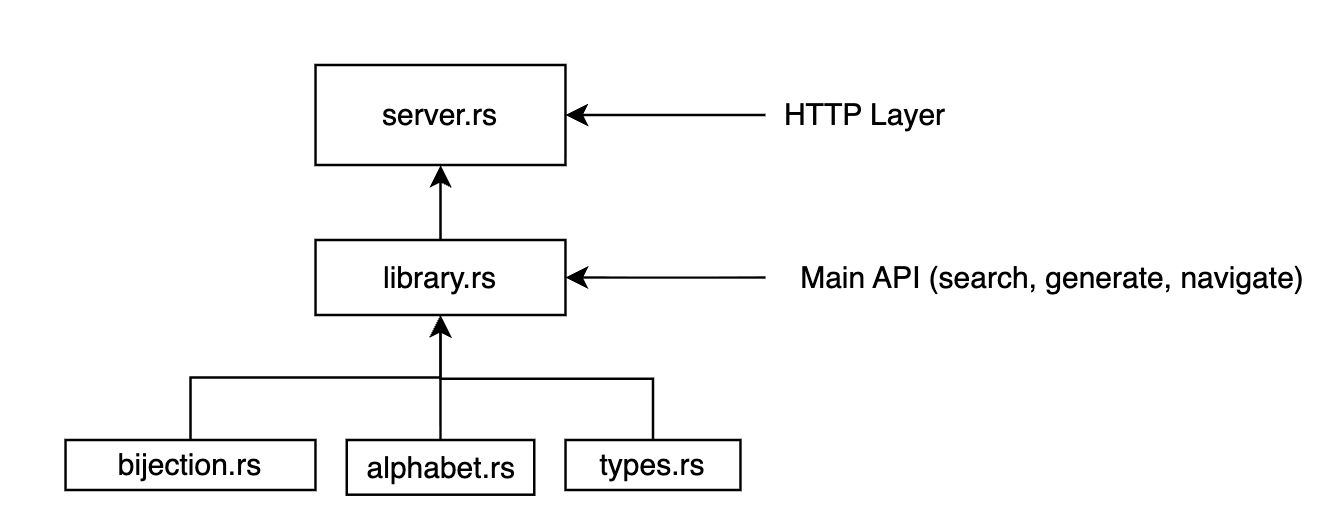

This required a clean separation of concerns. The bijection engine is agnostic to Kannada graphemes and operates only on an abstract set of N symbols for mapping sequences to and from addresses, while the alphabet module defines those symbols and the library module composes them into a usable API.

API Architecture design

The bijection module is pure mathematics. Give it a number, it gives you another number. The alphabet module is pure linguistics. It knows the 57,324 valid Kannada grapheme clusters and how to segment text into them. The types module defines what an address looks like, hierarchically and raw. They don’t talk to each other directly. The library module orchestrates.

If you wanted to build ಅಕ್ಷರ-ಮಂಟಪ for తెలుగు (Telugu), you’d replace alphabet.rs with Telugu grapheme clusters, adjust one constant (the cluster count), and rebuild. The bijection engine wouldn’t notice the difference.

III. Why Rust

ನಮಸ್ಕಾರ!

I’ve been writing Rust on and off for a few years (honestly only 2 lol), mostly for systems work and cryptography experiments. It felt like the right tool here for three reasons.

First, performance. The bijection engine does arithmetic on 6,300-bit integers. Every page lookup involves one multiplication and one modulo operation on numbers with nearly 2,000 decimal digits. Rust’s num-bigint crate handles this efficiently, and the language’s zero-cost abstractions mean I’m not paying for things I don’t use.

Second, the type system. When you’re juggling raw addresses, hierarchical addresses, grapheme indices, and page content, it’s easy to mix them up. Rust’s strong typing caught several bugs at compile time that would have been runtime mysteries in a dynamic language. A GraphemeIndex is not a PageNumber is not a RawAddress, and the compiler enforces this.

Third, and most importantly: Rust compiles to WebAssembly. The same codebase that runs as a native binary on my laptop can run in your browser. This turned out to be crucial.

IV. The Hosting Problem

I didn’t want to pay for hosting. This is a passion project, not a startup. No VPS, no managed database, no cloud bills. Just me, infinity, and a browser.

The ideal was simple: GitHub Pages. Push HTML and JavaScript and GitHub serves it. Free, reliable, and requiring almost no maintenance. It was the dream of set it and forget it.

The problem was that the bijection engine is written in Rust. It runs as a server. GitHub Pages serves only static files. It cannot run arbitrary code. Pushing a .rs file and expecting it to execute was not going to happen.

For a while, I considered using a free-tier backend to bridge the gap, but it felt like cheating. The library should be self-contained, able to work offline, and survive even if I eventually lose interest in maintaining servers, frameworks, or the kind of plumbing that usually eats passion projects alive.

I wanted the code to run locally so anyone could spin it up on their laptop and have it work. And if a brave soul decided to host it on AWS for a different frontend, that was fine too. GitHub Pages, however, forced the issue. I had not even designed for hosting originally; it was one of those “I’ll figure it out later” problems, and now I had to confront it.

I could have made this a single mono-repo combining backend and frontend so it would run completely in the browser, but that would have collapsed the separation I wanted between engine, alphabet, and UI. Clean boundaries make the math, the linguistics, and the code easier to reason about. Infinity is complicated enough without adding unnecessary infrastructure to the mix.

V. The WASM Solution

WebAssembly (WASM) lets you compile languages like Rust, C++, or Go into a binary format that runs in the browser. The same Rust code, different compilation target. Your browser becomes the server.

I used wasm-pack to build the Rust crate into a WASM module, and wasm-bindgen to generate JavaScript bindings. The result: a .wasm file and some glue code that the frontend can import directly.

The architecture splits into two modes:

Development: Frontend → HTTP requests → Axum server → Rust (native)

Production: Frontend → direct calls → WASM → Rust (in browser)

During development, I run a local Axum server. The frontend makes HTTP requests, the server responds with JSON. Normal web architecture. This is easier to debug, and hot-reloading works properly.

In production (on GitHub Pages), there’s no server. The frontend loads the WASM module and calls Rust functions directly. The bijection engine runs in your browser tab. When you search for text, your machine computes the 6,300-bit multiplication. When you browse to a random page, your machine generates it.

The frontend detects which mode it’s in automatically:

const USE_WASM = import.meta.env.PROD

This is not the cleanest architecture. There’s some code duplication between the HTTP API and the WASM bindings. Edge cases exist that I’ve been lazy about handling. But it works, and it costs nothing to run. More on that later.

VI. The Frontend (A Confession)

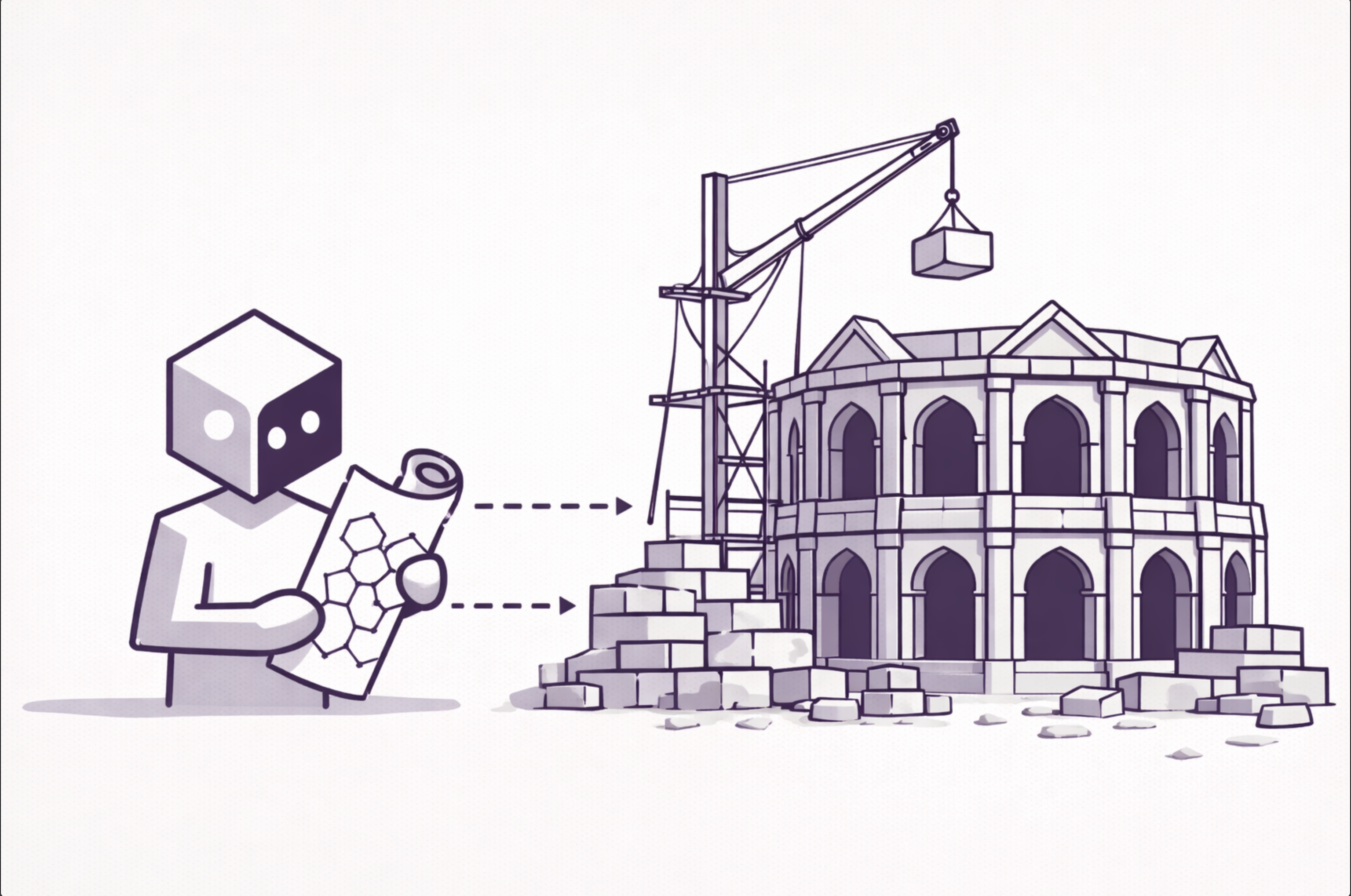

I’ll be honest: the frontend was mostly Claude. The part of the system that most people will see first is the part I understand the least.

I know enough HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to be dangerous, but not enough to build a reactive UI with history management, download features, and proper state handling. SvelteKit was recommended as a good framework for this kind of project. I’d never used it.

So I described what I wanted, Claude generated components, I tested them, we iterated. The search interface, the page display, the hierarchical address parsing, the “download book” feature that zips 410 pages into a text file. Claude wrote most of it. I reviewed, adjusted, occasionally rewrote when something felt wrong.

Is this cheating? I don’t think so. The core of the project, the mathematics, the linguistic modeling, the bijection engine, that’s mine. The frontend is a delivery mechanism. I could have spent months learning SvelteKit properly, but I wanted to ship something. Claude was a force multiplier.

The design goal was minimalist: dark background, clean typography, let the infinite text breathe. No clutter. Scholarly, maybe even a little austere. I think it achieved that, though I’m biased.

VII. The Dead Conjunct Problem

I thought I was done with the alphabet.

I had enumerated fifty-seven thousand grapheme clusters. Every consonant, every vowel sign, every conjunct I knew how to generate. The engine was bijective, the math was clean, the mappings were invertible. In theory, everything in Kannada had a place.

Then I showed it to a friend, and the search came back empty.

For a moment, I assumed it was a bug in the frontend. Then in the API. Then, briefly, something worse. If the engine could miss valid text, that meant a gap in the logic itself. And that would have defeated the entire point. A library that forgets is not infinite. It is just large.

The mistake turned out to be smaller, and more embarrassing.

In Kannada, consonants combine using a halant (್) to form conjuncts. I had handled those. What I had missed were conjuncts that themselves end in a halant.

Dead conjuncts.

No trailing vowel, no implicit sound to lean on. They show up all the time in transliterated English words and Sanskrit terms.

Visually, they behave like single units. Linguistically, they are single units. Internally, they are four code points long.

And they were not in my alphabet.

Damn.

Once I saw it, I could not unsee it. There were 1,296 such cases missing. Not theoretical corner cases, just things I had not thought hard enough about. I added them, recomputed the constants, rebuilt the engine, and the holes closed themselves. Infinity rearranged, and everything landed somewhere again.

In retrospect, the math itself had been fine. What was wrong was the way I had modeled the language, and I hadn’t realized how much I was leaning on that abstraction until it broke.

That realization stuck, mostly because of how easy it was to confuse something that was formally complete with something that actually respected how a script gets used. Kannada isn’t a neat symbol table; it has history, habits, and exceptions that stop being exceptions the closer you look.

There are almost certainly more things I do not yet know about Kannada. That is not a flaw in the project. It is the price of taking a living language seriously.

ಅಕ್ಷರ ಸಣ್ಣದು, (ಅರ್ಥ) ಅನಂತ

The letter is small; meaning is infinite.

VIII. For Contributors: A Map

If you want to fork this for another language, or just understand how the pieces fit together, here’s a quick map:

backend/src/

├── bin/server.rs → Axum HTTP server (dev only)

├── lib.rs → Library entry point

├── alphabet.rs → Grapheme cluster definitions

├── bijection.rs → Modular arithmetic engine

├── constants.rs → Page/book/shelf dimensions

├── library.rs → Main API: search, generate, navigate

├── types.rs → Address types and conversions

└── wasm.rs → WASM bindings for browser

frontend/src/

├── lib/api.ts → Dual-mode API (HTTP or WASM)

├── lib/wasm/ → Compiled WASM module

└── routes/ → SvelteKit pages

To add a new language, the steps are:

-

Create a new alphabet file with your script’s grapheme clusters. This is the hard part, requiring linguistic knowledge of how the script works.

-

Update the constants. The cluster count changes the modulus N, which changes the multiplicative inverse, which changes everything downstream. But the engine recomputes this at startup, so you just need to change one number.

-

Rebuild the WASM module with

wasm-pack build. -

Deploy.

The bijection engine doesn’t care what script you’re using. It only cares how many symbols exist. Swap the alphabet, and you have a Library of Babel for a different language.

If anyone actually does this, please let me know. I’d love to see ಅಕ್ಷರ-ಮಂಟಪ’s cousins in other scripts.

IX. The Visuals

I needed images for the site. A banner, some decorative elements, maybe illustrations for the blog posts.

I could have used Midjourney or DALL-E or one of the big commercial generators. But Stable Diffusion felt more appropriate. Local, open-source, in the spirit of a project that runs entirely in your browser. I generated what I needed. The quality is acceptable, not stunning. Art direction is not my strength.

A future version might have more visual richness. Generated manuscript aesthetics, maybe. Visualizations of the address space. But that’s for another day, another burst of motivation.

A Black Hole for the Text

X. A Note on Constraints, Time, and Decay

I did not begin this project with deployment in mind. I was thinking about bijections, grapheme clusters, and whether it was even coherent to speak of a Library of Babel in a script like Kannada. Hosting entered the picture much later, when the mathematics had already settled into something I was unwilling to disturb.

It would be easy to say that this was poor planning. In a sense, it probably was. But engineering is rarely a straight line from requirements to implementation. Constraints appear gradually, and the interesting decisions are made at the moment you decide what not to bend. When hosting became a concern, I chose to adapt the delivery rather than the core. That choice shaped everything that followed.

Some of the consequences are obvious. Running large integer arithmetic inside a browser tab is not fast. Maintaining both an HTTP server for development and WebAssembly bindings for production introduces duplication. The architecture is more complex than a single JavaScript application would have been. All of this is true, and none of it is accidental.

This project has no latency budget. It has no scaling story. It does not need to survive a sudden influx of users or justify its existence in operational terms. What it needs is correctness, separability, and the ability to exist without ongoing infrastructure or attention. The engine should continue to make sense even if the frontend changes, even if the web framework I used is deprecated, even if I lose interest for a few years and return to it later with different tools.

That last point matters to me more than it probably should. Software ages. Frameworks fall out of fashion. Browsers change. If SvelteKit disappears someday, the UI will change. If WebAssembly evolves, the bindings will change. None of that should require rethinking the mathematics. The separation exists precisely so that the outer layers can decay without taking the core with them.

This is not an attempt to build something timeless. It is an attempt to build something that can tolerate time.

XI. What’s Next

The library is live. The code is open. You can visit it now:

In the final post, I’ll step back from implementation details and reflect on what this project taught me. About infinity, about language, about the strange satisfaction of building something useless and beautiful.

If this survives longer than my enthusiasm for maintaining it, I will consider that a success.

Next: Post 5 — Reflections on Infinity