Exploring the Infinite Libraries

This is the second post in a series documenting the conception and implementation of ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ (Akshara-Mantapa), my attempt to build Borges’ Library of Babel in Kannada. The series walks through philosophy, linguistics, mathematics, and engineering, in that order, mostly.

The Series:

೧. The Dream of Ananta: why infinity, why Kannada

೨. Exploring the Infinite Libraries: You are here

೩. Taming Infinity: the mathematics of bijection

೪. Engineering Infinity: Rust, WASM, and making it run

೫. Reflections from Infinity: what I learned

I. Previously, on this series

In the last post, I rambled about aurora borealis, infinity, LLMs as sculptors of bounded infinity, and why I wanted to build a Library of Babel in ಕನ್ನಡ. Philosophical throat-clearing, mostly. Important throat-clearing, but still.

Now let’s get practical. This post is a hands-on guide to two infinite libraries: Jonathan Basile’s original Library of Babel, and my Kannada implementation, ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ (Akshara-Mantapa). I want you to actually use them. Open them in another tab. Click around. Get lost.

Then I’ll explain why Kannada makes everything harder.

II. Jonathan Basile’s Library of Babel

To understand what my website is about, you should first understand where the original inspiration came from. And… it gets a bit esoteric.

Go there. Right now. I’ll wait.1

First Action: Browse Random

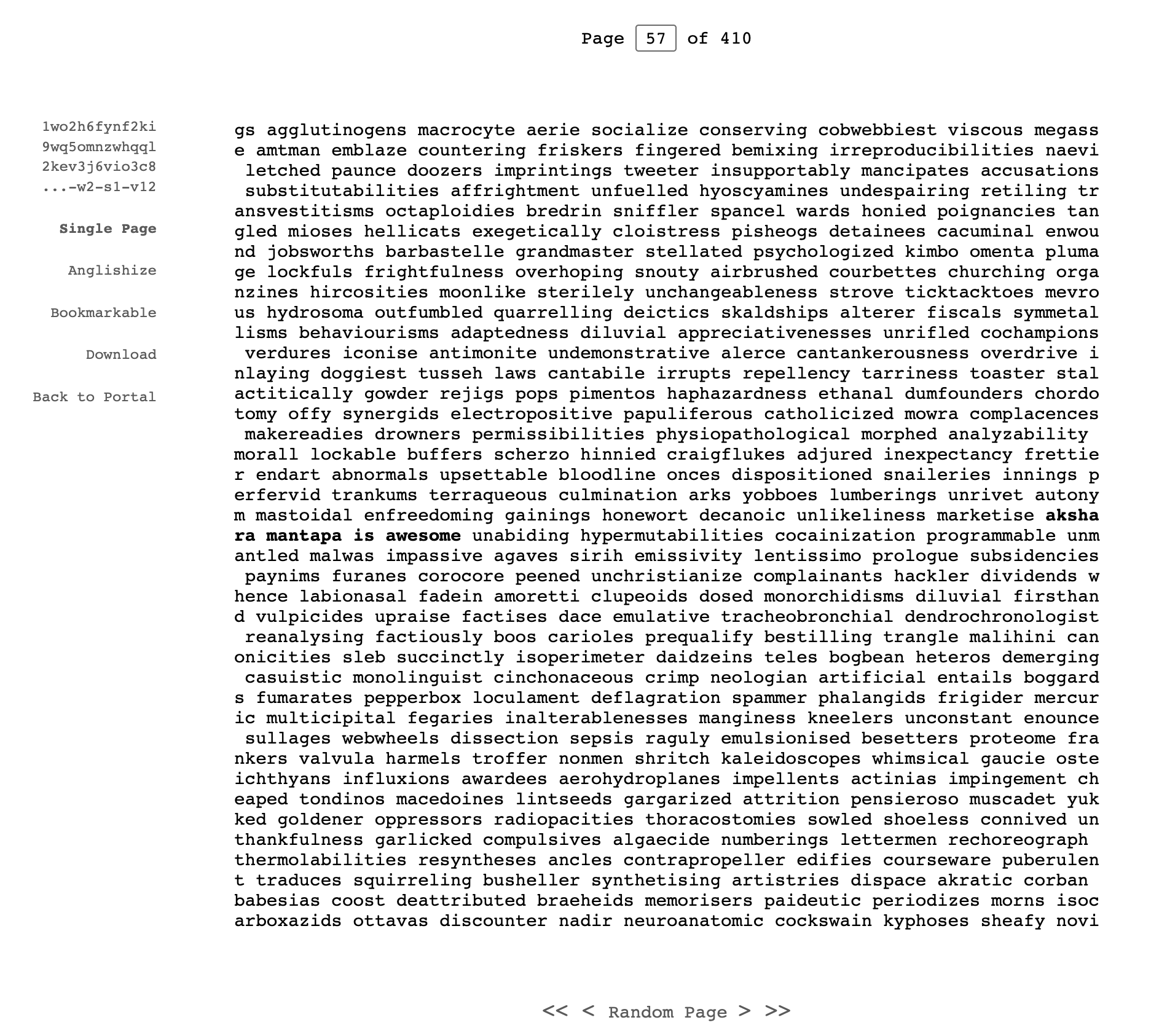

Click “Browse” and then “Random.” You’ll get a page. It will look like nonsense. That’s because it almost certainly is nonsense. The library contains every possible arrangement of 29 characters (26 letters, space, comma, period) across 3,200 characters per page. Most of infinity is noise.

But somewhere in there is the exact description of your death. The cure for every disease. A perfect biography of someone who was never born. Every lie and every truth, indistinguishable from each other. All expressed by 29 characters.

Can you find the fun text?

The Theory

You might think it’s just a trick, just a clever randomizer that generates a bunch of characters every time you browse. But no. It has “technically” mapped every possible sequence of words into a library that can run on your browser. Clever, no?

Basile has written about his approach on the website. I recommend reading his explanation. It’s elegant and doesn’t require a math degree.

→ Theory page on libraryofbabel.info

The Search Feature

The random page… seems… boring, right? I mean, are we supposed to be impressed by the fact that it can produce random gibberish? But there’s an extension to it. The Search part. And this is fun.

In the search box, type any text (up to 3,200 characters) and the library will tell you exactly where that text exists. It doesn’t “search” through the library. The text was always there. The search just reveals the address.

Try this:

I am [insert_name] and I want to know if I’m going to be wise by [insert_birth_year + 40]

This is invertibility. Given any content, you can find its address. Given any address, you can find its content. Bidirectional. Omniscient.

The Picture Library

If the text library didn’t break your brain enough, Basile also built a picture library. Every possible image that can be rendered in a certain resolution. Every photograph that could ever be taken. Every face that will never exist.

Face of Infinity

It’s even more incomprehensible than the text library, because we process images faster than text. The noise hits differently.

III. ಅಕ್ಷರ ಮಂಟಪ (Akshara-Mantapa)

→ sanathnu.github.io/Akshara-Mantapa

This is my implementation. Same concept, different script. The Library of Babel, but in Kannada.

The Structure

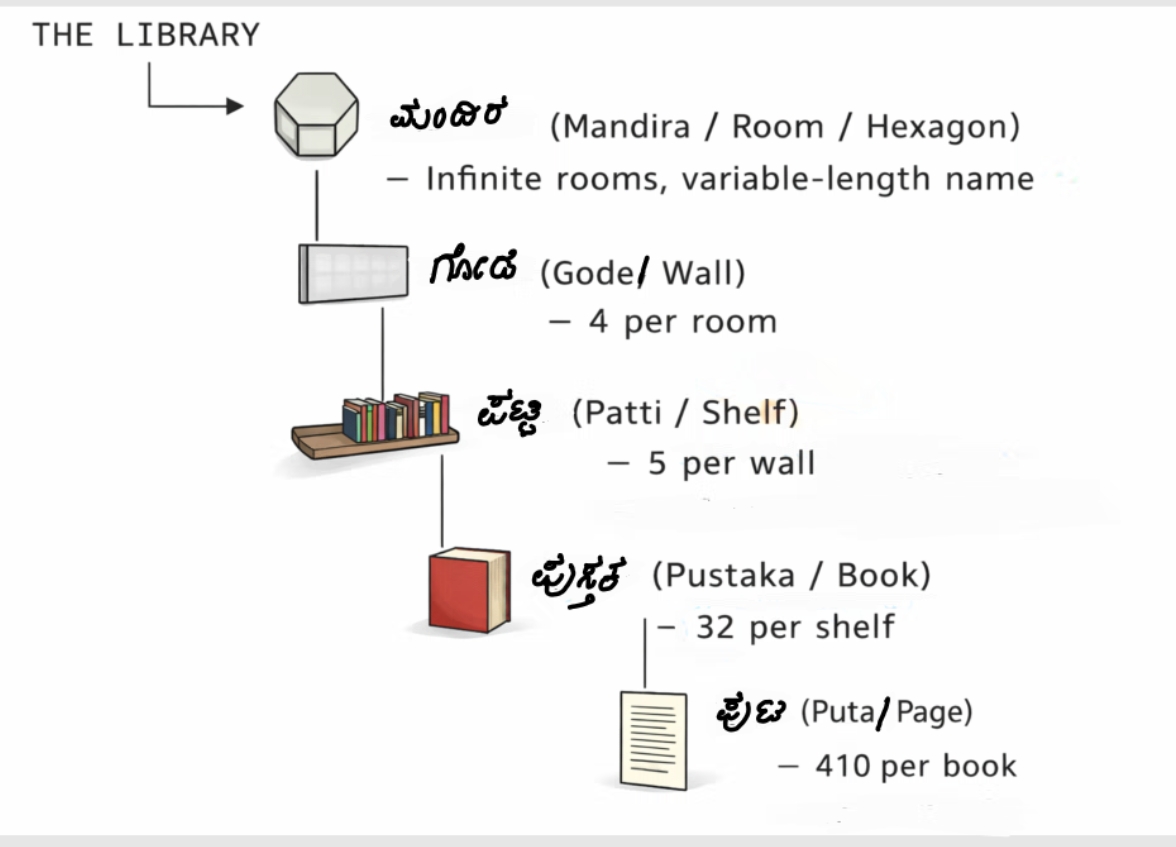

I tried to stay faithful to Borges’ original vision. The library is organized hierarchically:

| Kannada | English | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| ಮಂದಿರ | mandira | room |

| ಗೋಡೆ | gode | wall |

| ಪಟ್ಟಿ | patti | shelf |

| ಪುಸ್ತಕ | pustaka | book |

| ಪುಟ | puta | page |

So an address might look like: mandira.gode.patti.pustaka.puta. For small enough addresses, the room name renders in Kannada script itself.

Structure of Address

Why 400 Characters?

Basile’s library uses 3,200 characters per page. Mine uses only 400. Why?

Kannada is not English. It’s not just “different letters.” The character space is vastly larger. Where English has 29 symbols, Kannada has approximately 57,000 valid grapheme clusters. I’ll explain this properly in a moment, but the short version: if I used 3,200 characters with 57,000 possibilities each, the address space would become computationally unwieldy. 400 characters keeps things manageable while still being meaningfully infinite.

First Action: Search Something

If you read Kannada, try searching for something meaningful. A line from a poem. ನಮಸ್ಕಾರ. Your name in Kannada. A phrase from a Kuvempu verse. The library has it.

If you don’t read Kannada, that’s okay too. Browse random pages. Enjoy the alien beauty of the script. Those curves and loops contain everything that could ever be written in a language you may never learn. There’s something poetic in that.

Download a Piece of Infinity

You can download any page as a text file. You can download an entire book (all 410 pages). Keep a slice of infinity on your hard drive. A finite artifact from an endless library.

I like the idea of someone having a folder somewhere called “infinity_backup (ಅನಂತ_ಬ್ಯಾಕಪ್)” containing gibberish that happens to be the complete works of a ಕನ್ನಡ poet who will be born in 300 years.

IV. The Core Difference: Characters vs Graphemes

When I first started thinking about how to port Basile’s algorithm to Kannada, I assumed the hard part would be the math. I was wrong. The hard part was understanding what a “character” even means.

English is deceptively simple. Twenty-six letters, plus space, comma, period. Basile uses 29 symbols total. Each character is atomic. k is k, a is a, and ka is two characters. You can enumerate them, count them, map them to integers. Clean. Conquerable.

Kannada refused to be conquered so easily.

What looks like a single “letter” in Kannada is often a combination of multiple Unicode code points that merge into a single visual unit, what linguists call a grapheme cluster. I think of it as ಅಕ್ಷರದ ಆತ್ಮ (the soul of the letter): components that lose meaning apart but become whole together.

Let me show you what I mean:

The character ಕಾ (kaa) looks like one letter. Your eyes read it as one. But underneath, it’s two code points holding hands: the consonant ಕ and the vowel sign ಾ. They combine visually but live separately in computer memory. This is how Indic scripts think, not in isolated atoms, but in relationships.

And it gets worse. Kannada has:

- 49 base consonants

- 14 vowels

- Vowel signs (matras) that attach to consonants

- The halant (್) which kills the inherent vowel

- Conjunct consonants (like ಕ್ಷ, ತ್ರ, ಸ್ತ್ರ)

- Anusvara (ಂ) and visarga (ಃ)

When you enumerate all valid combinations, all the ways these can legally combine, you get approximately 57,000 grapheme clusters.

Not 29. 57k.

Why This Changes Everything

In Basile’s library, the math is: 29^3200 possible pages.

In my library, if I naively used 3,200 positions: 57000^3200 possible pages. That’s… not great for computation.

So I reduced to 400 characters: 57000^400 pages. Still infinite for all practical purposes. Still containing everything that could ever be written in Kannada. But tractable.

The real challenge wasn’t just the number, though. It was segmentation. Given a string of Kannada text, how do you split it into grapheme clusters correctly? You can’t just iterate through Unicode code points. You need to understand which combinations are valid, which code points attach to which, where one cluster ends and another begins.

This required building a proper segmentation algorithm, one that could look at a stream of Kannada text and carve it into meaningful units. The solution involved greedy longest-match parsing and a lookup table of all valid clusters. It sounds simple when I say it like that. It wasn’t. But that’s a story for the next post.

V. Next: Taming Infinity

So far we’ve played with two libraries. We’ve seen that Kannada’s script complexity makes everything harder. But I haven’t told you how the magic works.

How do you make infinity searchable? How do you ensure that every address maps to exactly one page, and every page has exactly one address? How do you do this bidirectionally, without storing anything, computing on the fly?

The answer involves:

- Bijective functions

- Modular arithmetic

- Multiplicative inverses

- 6,300-bit integers

- A thing I’m calling the “Babel Trilemma”

Go play with the libraries. Get lost. Then come back, and I’ll show you how they work.

→ libraryofbabel.info

→ Akshara-Mantapa

Next: Post 3 — Taming Infinity

-

If you’re up for it, read the original story too. ↩