Signal Chat Archaeology

Intro

So, I had this idea: since Signal is open source, I should be able to crack open my own backup and actually understand what’s going on inside, right? And it’s my data… the beauty of open source is that you don’t have to trust it blindly. You can inspect it, break it, maybe even learn something from it.

Also, there’s this weird irony: private data is… private. Which means if I don’t analyze it, no one else should be able to. I found a few backups of Signal in my laptop a few weeks earlier. I knew I wasn’t about to throw away this god-given chance to dig through my own digital mine.old from my own ore, you know?

I just whipped out one my Signal backup from my android phone, dated 2 years ago, and got the carefully encrypted password too. The structure of Signal backup was just an SQLite database and a collection of media files, which was encrypted.

I then stumbled upon this blog that laid out a couple of approaches. I seriously thought it would involve some john-the ripper style brute forcing, but it was simple enough. We are not in the dark ages of a chat app like PGPChatAPP; Signal’s community support and tooling definitely reinforced that.

From Android Backup (The First Stumble)

This was the main file that I had, and I wanted to try using this. The first pre-req was to create a backup file . Then, I tried using a called signal-back to extract the data. This was more than half a decade old, and I was really skeptical about the decrypting nature of a backup. Open source does move slowly, but I still wasn’t sure about this. But trusting the authenticity of the author (seemed to know what he’s doing, he does know ruby, which is one more language I don’t know lol), I pressed on.

Trial 1 (didn’t work)

Signal-back had a dependency on SQLcipher, which was a very interesting fork of sqllite with added encryption scheme. I tried installing it via

sudo apt-get install sqlcipher

This installed an old version, which is 3.15. which wasn’t supported by signal-back, and the only other option to do was build sqlcipher from scratch . This was also recommended by the blog post dude, which he said would upgrade sqlcipher from 3.15 to 3.31 or above. There wasn’t any other way apart from building. Hence feeling confident of myself, I ran these commands

1

2

3

4

# Build from source (following blog instructions)

git clone https://github.com/sqlcipher/sqlcipher.git

cd sqlcipher

./configure --enable-tempstore=yes CFLAGS="-DSQLITE_HAS_CODEC" make && sudo make install

Even when it asked for sudo permissions, I didn’t see what was happening (which will bite me back later), and assumed it had something to do with putting the binary in the /usr/bin folder. Then I tried to run

1

signal-back format -f CSV -o backup-android.csv <signal-XXX.backup>

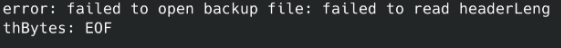

And it asked me to input a passcode. I was like, my Signal passcode was 30 digits long, where did I lose my 6 digs? 🫠. It didn’t run with the code I gave. Threw up some EOF error.

I figured that this was out of date and since I had the god like power of copilot with me, I tried to reverse engineer the source code, in hopes of figuring out how to change 36 digit to 30. After bunch of reading Go code and literally begging copilot to give me the answer, I got this:

To my surprise, to my utter surprise, the code wasn’t the problem. The 30-digit thing was actually in the README of signal-back all along. Man, sometimes I trust blog post authors more than the tool documentation🤦♂️.

My Linux Desktop’s Existential Crisis

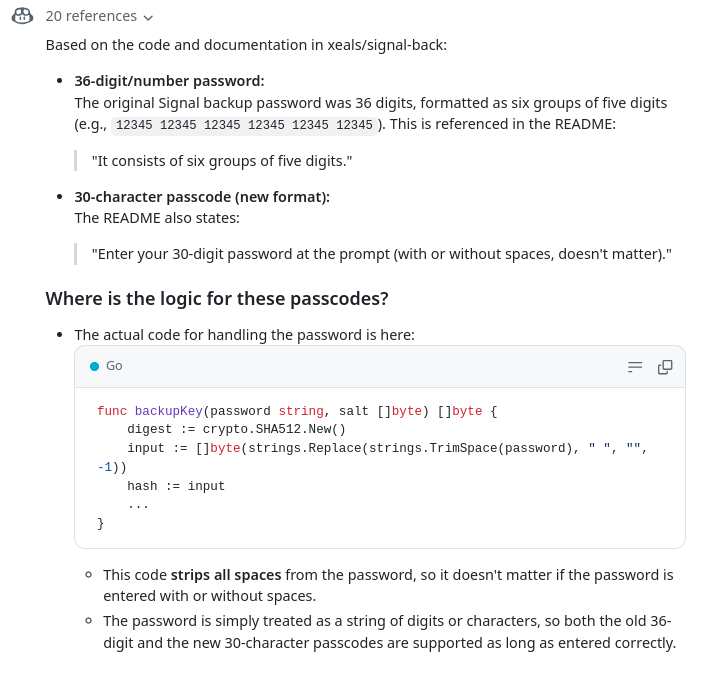

Then, completely unrelated (or so I thought), my KDE Plasma desktop started glitching out.And I thought the reboot should fix the problem. Famous. Last. Words.

Well, I was wrong, and after reboot, I lost my entire plasma screen, and just replaced by a black screen. This was the n-th time, a reboot didn’t solve my problem, but rather caused it .The irony wasn’t lost on me.

And a long debugging session with stackoverflow, I came upon this discussion, where the dude gave the problem and the solution.

I was like, “This is me, my friend. Thank you for having this problem!”

I then deleted all /usr/local/lib/libsqlite3*.* files. and this just reset my entire laptop. All my customization (virtual desktops, wallpapers) gone. Such is the glorious life on Linux.

This entire thing was a futility in debugging, I just gave up on the android backup file and tried my other hand on desktop.

Trial 2 (Didn’t work either)

Since I thought I had the Signal desktop version for linux, I thought I should be able to get the key and decrypt it easily! ( learning on the process than my signal chats were just encrypted with a key that is a sudo cat away from obliteration)

I tried to get the key from /<home_folder>/.config/Signal/config.json. But sigh, I realized that my config.json is messed up, because I tried to copy a previous signal backup from another linux distro to a new installation (which had worked, miraculously, but messing up the config file in the process)

I really didn’t have the time or the mood to figure out stuff from this at 3AM in the morning. Hence I gave up on this method also.

Trial 3 (Third time’s the charm!)

I finally came across signal-backup tools, which just decrypted my backup in 2 seconds. I just lost my mind.

I just ran this:

signalbackup-tools <backup_file> <passkey> --export RAWOUTPUT/

which gave me a dump of raw files! I was overjoyed. From there, it was just one more command away from getting the messages into a beautiful CSV file:

signalbackup-tools <backup_file> <passkey> --exportcsv messages=messages.csv

I had all the files and data, which had the following structure. (taken from the source code and from sweet, sweet devin thread)

| MessageTable.ID | MessageTable.MESSAGE_RANGES | MessageTable.REMOTE_DELETED | MessageTable.QUOTE_TYPE |

| MessageTable.DATE_SENT | MessageTable.FROM_RECIPIENT_ID | MessageTable.UNIDENTIFIED | MessageTable.ORIGINAL_MESSAGE_ID |

| DATE_RECEIVED | MessageTable.TO_RECIPIENT_ID | MessageTable.LINK_PREVIEWS | MessageTable.LATEST_REVISION_ID |

| MessageTable.DATE_SERVER | EXPIRES_IN | MessageTable.SHARED_CONTACTS | MessageTable.HAS_DELIVERY_RECEIPT |

| MessageTable.TYPE | MessageTable.EXPIRE_STARTED | MessageTable.QUOTE_ID | MessageTable.HAS_READ_RECEIPT |

| MessageTable.THREAD_ID | MessageTable.QUOTE_AUTHOR | MessageTable.VIEWED_COLUMN | MessageTable.NETWORK_FAILURES |

| MessageTable.BODY | MessageTable.QUOTE_BODY | MessageTable.RECEIPT_TIMESTAMP | MessageTable.MISMATCHED_IDENTITIES |

| MessageTable.QUOTE_MISSING | MessageTable.READ | MessageTable.MESSAGE_EXTRAS | |

| MessageTable.QUOTE_BODY_RANGES | MessageTable.TYPE | MessageTable.VIEW_ONCE | |

| PARENT_STORY_ID |

Once I had that CSV file, I immediately wrote a simple Rust script to get the statistics. Take on that, original author 1 – you write Ruby, I write Rust!

Data economics

So, once I had all that raw data, it was time to make sense of it. I ended up whipping out a Rust script to crunch the numbers on my chats – yeah, I also wrote a Python version, just because. You can find the full scripts over here in the gist.

In Signal’s backup schema, a “thread” is basically just a conversation, identified by a ThreadID. With that and the message timestamps, you can slice, filter, and analyze chats however you want. Granular-level control, baby.

Now, I’m not gonna reveal my Signal chats in public (I use Signal for a reason, man!). But it’s safe to say… they were substantial! We had a blast in 2023, Thread 17! I genuinely didn’t expect to communicate that much on this app. Makes me wonder how much more would show up in my WhatsApp backup.

Anyway, here’s a peek at the Rust code that did the work:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

fn analyze_signal_csv(filepath: &str, thread_id: Option<&str>) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let mut messages = Vec::new();

// Open the CSV file and read it

let file = File::open(filepath)?;

let mut reader = Reader::from_reader(file);

// Iterate through each row in the CSV

for result in reader.records() {

let record = result?;

// Get the thread_id from the record

let record_thread_id = record.get(4).unwrap_or("").to_string();

// Filter by thread_id if specified

if thread_id.is_none() || thread_id == Some(&record_thread_id) {

// Get date_sent from the record (assuming it's in the first column)

let date_sent_ms = record.get(1).unwrap_or("0").parse::<i64>()?;

// Convert from milliseconds to timestamp

let dt = Utc.timestamp_millis_opt(date_sent_ms).single()

.unwrap_or_else(|| Utc::now());

let date_sent = dt.format("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S").to_string();

messages.push(Message {

date_sent,

thread_id: record_thread_id,

});

}

}

// If no thread_id is specified, show overall statistics for all threads

if thread_id.is_none() {

println!("Statistics for all threads:");

}

// Group the messages by year

let mut grouped_by_year: HashMap<String, Vec<&Message>> = HashMap::new();

for msg in &messages {

let year = msg.date_sent[..4].to_string(); // Get the year from the date string

grouped_by_year.entry(year).or_insert_with(Vec::new).push(msg);

}

// Sort years and output the year-wise message counts

let mut years: Vec<_> = grouped_by_year.keys().collect();

years.sort();

for year in years {

let msgs = grouped_by_year.get(year).unwrap();

println!("{}: {} messages", year, msgs.len());

}

// Output total number of messages

let total_messages = messages.len();

println!("Total number of messages: {}", total_messages);

if total_messages > 0 {

// Earliest message date (if messages exist)

let earliest_message = messages.iter()

.min_by(|a, b| a.date_sent.cmp(&b.date_sent))

.unwrap();

println!("Earliest message date: {}", earliest_message.date_sent);

}

if thread_id.is_none() {

// Show stats for all threads

let mut thread_counts: HashMap<String, usize> = HashMap::new();

for msg in &messages {

*thread_counts.entry(msg.thread_id.clone()).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

println!("\nMessage counts per thread:");

let mut thread_list: Vec<_> = thread_counts.iter().collect();

thread_list.sort_by(|a, b| a.0.cmp(b.0)); // Sort by thread_id

for (thread, count) in thread_list {

println!("Thread {}: {} messages", thread, count);

}

}

Ok(())

}

This whole process really hammered home the software debugging lifecycle: curiosity -> pain -> pain -> pain -> happiness.

Retrospekt

I had a folder full of raw data, for which I had so tirelessly spent 2 hours debugging. You think with AI everything should be much faster no? Absolute dogshit. Turns out, even with all the AI hype, when you’re wrestling with half-a-decade-old open-source components and weird command-line tools, your ‘god-send claude’ is pretty much as clueless as you are . Absolute dogshit for this specific kind of problem.

But Deepwiki turned out to be interesting. It turned some boring documentation and code reading into a question answering session. Like a senior engineer who’s an expert in that specific source code, explaining with board diagrams how Signal works. Pretty Rad.

It probably saved me a few more hours of head-desking (and maybe, ironically, learning less about the nitty-gritty of code debugging on my own ).

I was able to learn a lot though. Not just relying on blog posts or source code, I was able to have a *pointer* to the code to read and problem to debug. Perplexity didn’t quite hit the mark, but it definitely cut down on the raw ‘search time’.

Ultimately, I’m happier that I actually got something out of this whole mess. AI or not, the data’s out, and that’s what counts.

Conclusion

Anyway, that’s how I spent my Tuesday night. 2 hours of pain for 2 seconds of success. The backup is decrypted, the stats are analysed, and my plasma desktop is rebuilt. Sometimes the journey is more interesting than the destination, I guess.

Ciao!