Books of 2024📚

Introduction

Well, there has been a fair amount of reading in 2024, and this is my review of it. I’ve read some painfully dull books, and some that lit my brain on fire. This year, certain genres hit something deep inside me - like an internal bell that vibrates through your mind when an idea really strikes home. That bell rang many times , and that, shows.

Through these pages, I wandered through science, philosophy, history, economics, and political science. Along the way, I learned something uncomfortable: everything you read, everything you think… it’s all temporary. Books that seemed life-changing last year barely left a scratch this year (except for that newfound skepticism). The futility of reading hit me hard. I kept asking myself “why push yourself?” Why this constant drive to learn and update yourself?

There were shelves on shelves of books on every conceivable subject…The late owner had read them all, and many of them were full in their margins with cross-references in pencil. There pigeon-holed desks and cabinets with literally thousands of compartments..These volumes were apparently coming in at the rate of 10 or so per week…For years, apparently, he had been endeavouring to keep up with everything that was being written—a Sisyphean task. Over all there were brown Holland sheets, a thin coating of dust, the moths dancing in the pale September sun. There was a faint aroma of mustiness, proceeding from thousands of 17th & 18th-century books in a room that had been locked up since the owner’s death. I never saw a sight that more impressed on me the vanity of human life and learning.

-Sir Charles Oman, On The Writing Of History 1939

I think I have found an answer for myself. A very personal one 1

Living in this technological rocket-ride of an era, I watch thoughts slip away very easily in this vast latent space created by our growing knowledge. There’s so much things running ephermally in our brains, and nothing to last. But here’s the thing: I believe we have an obligation - to this mind we’ve been given, to push it to its fullest potential. To truly try to grasp the breadth of human experience. And for me, that happens through books.

This piece is my attempt to map that 2024’s journey. The books that rocked my world, the ideas that shifted my thinking, and the thoughts that emerged along the way. Buckle up folks, its going to be a long one.

Quantum Leaps

Body of three

2024 started with me arming myself with “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, determined to approach new ideas with careful skepticism. I was going to be methodical - engage my System 2 thinking, check my cognitive biases, question everything. That was the plan, anyway. Then The Three Body Problem trilogy came along and completely demolished my carefully constructed walls of rationality.

Messed up Dimensionality of Calabi Yau Manifolds

Messed up Dimensionality of Calabi Yau Manifolds

I initially picked it up because of the upcoming show (which turned out pretty good, btw), but the concepts blindsided me. Complex intra-planet instantaneous communication through quantum particle-supercomputers? Multi-planetary system organizational problems? Alternative speculative technologies for FLT? Fresh takes on Fermi Paradox? Get outta here. I went all in, and it was a very satisfying surrender. There’s so much to unpack in there (my first hard-science fiction in nearly half a decade), and these ideas still feel relevant to the technological and ideological possibilities of this century. As someone on reddit said

And I completely agree with it lol. This set my standard in what I would like to want going forward. There’s multiple very lengthy philosophical detours into the state of mind going through a particular situation. I think it would overwhelm the 13 year old me, but now, it’s nice.

“It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair. To achieve moral awakening required a force outside the human race.” - Ye Wenjie, The Three Body Problem

A rational me from 2023 wouldn’t venture into this area of fiction. This is so alluring, that it made me forget that rule of mine. Very simulating and fun. A good read, I would suggest.

Young people are all the same. The more books you read, the more confused you become. - Cheng Lihua, The Three Body Problem

Can we talk about us?

I explored more concepts in space and consciousness. Embassytown, gave a new look into language and just inefficient and different it can be to communicate with/to some other intelligent being. It introduces a concept of linguistic engineering, and other minds of perception you know. It taught me (or rather reinvigorated my desire to understand) Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and Second order logic, and non-linear alien economies run on biorigging. The Sapir-Whorf idea that language shapes how we perceive reality gets a wild workout here, as the aliens literally cannot think thoughts they don’t have words for. It’s like 1984 turned spaceward. It’s like their language isn’t just how they communicate, it’s the actual OS their consciousness runs on .

“We have to establish our credentials as an explorocracy; so to survive and rule ourselves, we have to explore.” - Avice, Embassytown

Not just a cup of sci-fi tea, I’m afraid. The ideas are so fresh , that it felt like I could keep on studying alien language hypothesis like I did with Arrival lol. I find Miéville’s writing a bit daft in places, which, hilariously enough, reinforces the book’s whole point about language being an inefficient mess. Here I am struggling with human-to-human communication while reading a book about the impossibility of human-to-alien communication. Meta, right? Makes you wonder if we’ll ever truly understand each other, let alone some bizarre alien intelligence operating on completely different cognitive hardware.

Fear is a great teacher, no?

Blindsight and its sequel took things to another level entirely. These books are so densely packed with references, you’ll go blind trying to understand them all. It’s about space vampires, and zombies AND alien life (scientifically exist-able ones atleast). Imagine the trio!

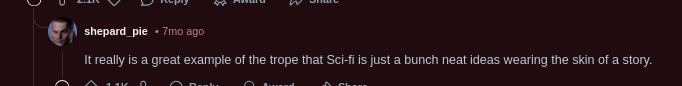

The vampire concept alone is worth the price of admission. Watts didn’t just throw in ‘space vampires’ for shock value; he built an entire scientifically plausible evolutionary history for them. These vampires have different brain structures giving them superior pattern recognition, and they survived on human blood for specific vitamins. But here’s where it gets wild—Watts actually addresses how vampires would avoid Kuru (the brain disease caused by human cannibalism) by developing resistance based on prion protein gene production. He even cites actual research papers on this stuff! Okay, now to hammer the book into your mind, consider these points.

The author created a mock scientific presentation on vampire discovery that feels disturbingly credible, complete with brain structure comparisons. The level of scientific rigor is mind-blowing, it’s artistic science with a passion. This kind of meticulous world-building hits my intellectual pleasure centers in ways that should probably be illegal.

Right is the vampire brain, left is our pleb human

Right is the vampire brain, left is our pleb human

Between these mind-benders, I touched base with classics like Rendezvous with Rama (my first Clarke) and Fahrenheit 451 (more drama than sci-fi, if we’re being honest). Clarke’s massive alien artifact drifting through our solar system gave me that sense of cosmic awe that only old-school sci-fi can deliver. It was clinical, to see astronauts behave like from Ad Astra. And Bradbury’s dystopia? Sure, it’s required reading, but it hit differently now. The whole “screens are destroying society” thing feels less like cautionary fiction and more like a documentary these days, lol. Neither blew my mind like the others, but each one added a tiny bit of ingredients into 2k24’s cosmic soup of ideas.

Consciousness cartography

Non-Fiction Dive: The Emperor’s New Mind

I went through some mind-bending territory here. Penrose’s Emperor’s New Mind was exactly as difficult as everyone warned me - thank god for my math and physics background or I’d have been completely lost. The time it took me to finish this book? Let’s not even go there. But I stuck with it because I needed to understand what’s coming with AGI. Not just the mathematical abstractions, but the fundamental physics and hardware that might make it possible. (Shoutout to PBS spacetime for making some of the quantum concepts click!)

“there seems to be something non-algorithmic about our conscious thinking. In particular, a conclusion from the argument in Chapter 4, particularly concerning Gödel’s theorem, was that, at least in mathematics, conscious contemplation can sometimes enable one to ascertain the truth of a statement in a way that no algorithm could.”

I still would like to make some comment on the nature of consciousness, as I understood from Penrose. He sees…computational structures in the logic of consciousness. He sees maths+uncertainty ruling the world. I would have totally agreed with him when I was 18.. but now, I have my doubts. Because I think there’s still a bunch of undiscovered mathematics left (my guess is somewhere in dynamic systems theory) , that will break down the laws of logic as we think of them now. And we will figure it out.

Fiction as Philosophy

Echopraxia, the successor to Blindsight, is pretty fun as hell too I mean. I wouldn’t worry much about the story part of this book, but goddamn, I thought a lot about the mind. This IS all about the mind. It’s building more on evolution theory and more on future mental models for thinking and computing. There’s this concept of distributed computing conscious minds, called the ‘Moksha mind’ (what nice naming right?), who have transcended reality or something? Just to put myself in their minds is epic as maniacal.

“Fifty thousand years ago there were these three guys spread out across the plain and they each heard something rustling in the grass. The first one thought it was a tiger, and he ran like hell, and it was a tiger but the guy got away. The second one thought the rustling was a tiger and he ran like hell, but it was only the wind and his friends all laughed at him for being such a chickenshit. But the third guy thought it was only the wind, so he shrugged it off and the tiger had him for dinner. And the same thing happened a million times across ten thousand generations - and after a while everyone was seeing tigers in the grass even when there weren’t any tigers, because even chickenshits have more kids than corpses do. And from those humble beginnings we learn to see faces in the clouds and portents in the stars, to see agency in randomness, because natural selection favours the paranoid. Even here in the 21st century we can make people more honest just by scribbling a pair of eyes on the wall with a Sharpie. Even now we are wired to believe that unseen things are watching us.”

― Peter Watts, Echopraxia

There’s something pessimistic about this paragraph, and enthralling at the same time. This teaches me more about evolution than when I discovered the Wolf/ Bunny simulations (Check it out, it’s cool).

Beyond Human Cognition

The vampires I talked about earlier? There’s an interesting insight I got from this book. And it bothers me. Here it is. There is a badass vampire named Valerie, who was originally bred to be a high level quant, and originally kept in like a human-controlled vampire prison. One of the most chilling concepts I encountered is the idea of communication without words and specifically, how Valerie might have escaped her confinement without ever directly interacting with other vampires.

Photo Credits Keenahmee@Deviantart

Photo Credits Keenahmee@Deviantart

Imagine this scenario: Valerie leaves nothing but “X+2B” scrawled on a wall, or perhaps just a single line drawn at a specific point in a hallway. Another vampire passes by, notices this seemingly random marking, and CLICK! Through sheer intellectual superiority, it immediately grasps the entire escape plan. No conversation needed. No planning sessions. Just one symbol, and a perfectly coordinated prison break unfolds. Because logic speaks volumes before emotions does.

That, my friend, is terrifying as hell for me. This is where the true horror of Watts’vampires lies. These aren’t the romantic, tortured souls of popular fiction (hi dracula!) They’re predators first, predators who hunted humans before we developed civilisation, whose minds operate on a plane so far beyond ours that their simplest communications are imperceptible to us. Like mathematical savants sharing elegant proofs that need no explanation to those who understand.

What’s truly terrifying is the implication: What if there are patterns and communications happening around us constantly that we’re simply too limited to perceive? What if our evolutionary “superiors” are exchanging complex ideas through means we can’t even recognize as communication? Like ants trying to comprehend human language, we might be fundamentally incapable of even recognizing that a conversation is taking place. It’s brilliant existential piece of tinkering I’ve read in a while.

“people have an unfortunate habit of assuming they understand the reality just because they understood the analogy. You dumb down brain surgery enough for a preschooler to think he understands it, the little tyke’s liable to grab a microwave scalpel and start cutting when no one’s looking.” ― Peter Watts, Echopraxia

It’s fascinating that beyond your emotions, there’s a whole lot of consciousness to be explored. While we have this moto of ‘You only live once’ and do some really funny quirky things…why don’t we want to live in a different mind? Be less….human? To really put myself into the consciousness of fictional vampires itself is a mind experiment that I long to do. It helped me think a lot about the mind, and how consciousness might actually work.

Silicon economies

Siren’s Tune: The Economic Refrain of Data

From there on, we come to the big baddies of non-fiction… I thinking about power and humans, spurred by a video of CGP grey on power. I fell into ‘Who owns the future’, a terribly insightful book. A hard book yes, but a good one. There’s concepts of Siren Servers, data-economies, and how current economic systems are rigged for zero-sum, winner-takes-it-all, non-linear games. I’m not going to bore you all with the details of this book. Go read my post

A point of interest for me currently is how he points out that ‘Siren servers’ radiate risks outside the system into the broader economy. I can equate this to Nicholas Taleb’s concept of Fragile systems (an anthesis of anti-fragile systems) He proposes a new way of economic thinking… based on the value that individual controls. A concept of ‘Data as labor’. Very very intriguing idea.

Democracies must be structured to resist winner-take-all politics if they are to endure. That principle applied in the network age leads to periodic confrontations between competing mirror-image big data political campaigns. It is a fascinating development to watch. ― Jaron Lanier, Who Owns the Future

As the seed of this ‘data-based-view’ slowly transmuted me, I wanted to learn more about economies. I’m not a trained economist, but after reading the Undercover economist and Data and Goliath, I realize that there’s a co-relation?(I know, I have had 3 books teach it to me lol😂). The economist, can also see a future in this myriad of connecting dots. I kinda had had a love-hate relationship with Big Data and analysis and this was cleared in how our mind perceives stats. Data mining is an art in itself. Statistics are the shovels, and the machine learning models are the smelters to get you the gold.

These “agents” have a lot of monitors eh?

These “agents” have a lot of monitors eh?

Scientific big data, like data about galaxy formation, weather, or flu outbreaks, can be gathered and mined, just like gold, provided you put in the hard work. But big data about people is different. It doesn’t sit there; it plays against you. It isn’t like a view through a microscope, but more like a view of a chessboard. ― Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Everybody Lies

I like another quote from another book ‘Everybody Lies’ and the author is being very optimistic lol.

The future of data analysis is bright. The next Kinsey, I strongly suspect, will be a data scientist. The next Foucault will be a data scientist. The next Freud will be a data scientist. The next Marx will be a data scientist. The next Salk might very well be a data scientist. ― Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Everybody Lies

This data economist thing can also see the future in data. The ideas, the thinking. I didn’t think it had as much as a hit as Dataclysm which I read in 2023, but okay, this sure has some weird insights? Not all data is created equally, In regards to the human behaviour, I got an interesting quote.

Never compare your insides to everyone else’s outsides (not by the author, but a good quote but by Anne Lammott)

And yeah,’Everybody lies’.

Solving DP problems

The mindless machinery of economics, as Taleb often points out, is something that really clicks when you start to understand how deeply entrenched it is in our systems. We have to solve the ‘Data-Power’ (DP) problem. Add to that the “Big Data guys” (Bruce Schneier, anyone?), and it becomes clear that we’re living in an information-centric age of power. The real drivers of influence today are no longer just wealth or muscle—it’s all about who controls the data, the algorithms, and the narratives that shape our world. We’re talking about power being exerted on an entirely different plane now.

But then, I contrast all of this with what I read in Our Oriental Heritage at the end of the year, and something starts to feel almost nostalgic. In ancient times, power was simpler to hold. It came down to money, manpower, and territory. It was about who had the most soldiers, the most resources, or the best trade routes. Power was direct, tangible. Fast forward to today, and the landscape is so much more complex. The “attack surface” is vast: information flows everywhere, and manipulation can be done with a keystroke. To navigate that, you’d think that the people in charge would need some kind of superhuman intelligence. Maybe an IQ of 140 is the new baseline. The sheer scope of what’s at play now demands a different kind of intellect.

But then again, the thought creeps in: What if we’re just one misstep away from disaster? Sure, we’ve reached new heights of complexity and power, but we could easily spiral into chaos. One wrong move with nuclear tech, one too many unchecked artificial intelligentsia, and boom ,we’re back to the stone age.

Still, looking back at this period, let’s say around 2024 , I think I’ll remember it as a time of economic awakening for me. Things are shifting fast. The human work structure is undergoing a massive transformation. Programs with greater intellect are beginning to reorganize the human effort pyramid. I don’t even know what work is going to be like in 20 years2 And with that, huge economic shifts are on the horizon. The future of this age of silicon intelligence is fascinating—and terrifying. It’s like watching the groundwork for a new economic reality being laid before our eyes. Fun stuff!

Civilization in the rear view

Germs and Steel

Fed up with the modern distopian analysis are we? Let’s get into some lore. I’ve had this bit of retrospection kindled recently, and it all started with diving into ideas about power and history. Guns, Germs, and Steel—a book that sat on my shelf for way too long—finally made its way into my hands, and damn, it didn’t disappoint. Sure, the sections on cultures were a bit dry (I get it, it’s a lot of detail), but the sheer scale of history, the endless patterns, the hundreds of incidents that have shaped us, honestly, it’s overwhelming. It’s wild how much is out there, just waiting for you to unpack.

“All human societies contain inventive people. It’s just that some environments provide more starting materials, and more favorable conditions for utilizing inventions, than do other environments.” ― Jared Diamond, Guns,Germs and Steel

I was exploring our very old DJ Peach Cobbler and his ideas on the Aztecs and Spanish Inquisition, and it started a whole lot of history tour for me. I didn’t know where I was headed, but it took me on a full-blown history tour, and suddenly I’m knee-deep in genocidal cultures and figuring out why Australia is basically life on hard mode. Like, did you know that the Fertile Crescent didn’t stay fertile? It’s crazy to think about how civilizations rise and fall, and how places we once thought would stay rich with resources are now barren. There are so many of these little nuggets of history that you stumble upon that make you rethink everything.

The Meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma Painting

The Meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma Painting

“One way to explain the complexity and unpredictability of historical systems, despite their ultimate determinacy, is to note that long chains of causation may separate final effects from ultimate causes lying outside the domain of that field of science.”

Presents from the Past

Next, I picked up Our Oriental Heritage, a classic (albeit outdated) on non-Western history. It’s part of a series I’ve been meaning to start for a while, and it took me two months to get through. Honestly, I’m glad I stuck with it, because this thing opened up whole mental doorways. It was like, the more I learned, the more I realized how little I knew. It’s sobering, you know? You see the rise and fall of civilizations, all these grand ideas and empires that are now just dust, and it makes you wonder about the vanity of our own accomplishments. We think we’ve figured it all out, but in the grand scheme of history, we’re just another blip.

And then, Durant, in all his wisdom, dedicates 200 pages of this behemoth to India, the country I was born in. That hit different. Living in India, I’ve only ever seen the country from the “inside”—the endless chaos, the crowd-driven noise, the overwhelming population, the dysfunction. I’ve given up on a lot of it, honestly. You get used to it. Rarely can I take a perspective of India from outside, because you know, my entire thought process has been INSIDE the country I am being born in. . It’s like seeing your own reflection from a different angle for the first time. It’s kind of mesmerizing, actually, to see how the very culture I’ve lived in shaped so much of the West.

“There is hardly an absurdity of the past that cannot be found flourishing somewhere in the present” ― Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage

I’m already deep into making notes about this book, dissecting all the ideas, and honestly, it’s a fun dive into history. Durant’s a pleasure to read, even if sometimes he’s too idealistic or outdated. But you can’t deny the insight he offers about the human condition. History has an axe to grind with the modern, cosmopolitan individual—we think we’re above it all, but are we really? As much as we try to separate ourselves from the past, it’s always there, lurking in the present.

Fiction transmutation

I think I’ve become more emotional over the years, and I can’t lie, it’s been a bit of a revelation. There’s been a steady rise in my appreciation for artistic works. It’s funny because, back in the day, only the grand, the sweeping stuff really awed me. I had my fiction phase earlier, but now…now, I get it. This year was something else. Slaughterhouse-Five hit me in a way I didn’t expect. It’s such simple writing, yet it lands. I knew Kurt Vonnegut from that ‘Structure of Stories’ video, but that was about it. So, I was mildly surprised when I found out it was a science fiction book. I was like, “Okay, sure, I’ll go along with this”, and suddenly I’m deep into the absurdity of a soldier-turned-optometrist, his wife, and the bizarre journey that unfolds. It was the kind of weird I wasn’t prepared for.

Honestly, it brought up some of the thoughts I had in this post about war. It’s the way Vonnegut breaks down a scene so dispassionately that even someone like me, the “get-on-with-it-guy”, found myself thinking twice about certain moments. And the bombing of Dresden? He describes it in reverse, and let me tell you, it’s the most beautiful anti-war statement I’ve ever read. It just sticks:

American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France, a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation.

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new.

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, Billy Pilgrim supposed. That wasn’t in the movie. Billy was extrapolating. Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed. ― Kurt Vonnengurt, Slaughterhouse-Five

The way this scene unfolded—it wasn’t just a moment in the book. It formed an image, one that hit me just as much as that haunting scene in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. It’s the same feeling: everything doesn’t really matter in the end. It shook me from my comfortable ivory tower of rationality, got me thinking in ways I hadn’t in a long time. I didn’t realize, until the very end, when I read a quote on a youtube video, that actually, the entire science fiction story might be made up. It was this dude in particular…that made me rethink twice about the book.

Okay, okay… enough about Slaughterhouse-Five before I lose you, because I know you probably won’t read the book anyway. But seriously, it had an effect.

Thoughts From My Ivory Tower of Rationality

So that’s my tryst with books in 2024. Wild ride, right? Looking back at all this intellectual chaos, I realize something kinda funny – I started the year trying to be this super-rational thinker with but ended up getting my mind completely blown by space vampires and ancient civilizations. Talk about a plot twist.

Learning to think about old physics for a new mind and trying to get a vision of reality, it’s fun. It’s strange. I still want to explore IIT (Integrated Information Theory) and think about the problem of Hard Consciousness (I know what I’m doing here lol) As I look back on this mental journey, I can’t help but think that consciousness operates like some strange attractor—unpredictable but patterned, drawing us toward questions that we can’t quite express yet. What if, like ants trying to solve calculus, we’re missing entire dimensions of understanding? Only time…will tell.

Durant’s civilizations rise and fall with a rhythm we can barely perceive. Yet in this punity and vanity of our accomplishments, there’s something beautiful about the attempt. Each book is another probe into the dark, another way to push against the boundaries of what this human mind can grasp. This year, I started with the intention of being rational, but I’ve ended up somewhere far more intriguing. I’ve grown emotionally in ways that would’ve embarrassed my former, “think-it-out” self. I’ve let vampires lead me into space, and aliens tie to the problem of loneliness in space. I’ve let the backwards bombing of Dresden hit me where I live. I’ve looked at my own culture from the outside and felt both estranged and enlightened.

So as we approach the end of the 21st century’s first quarter, I no longer see myself as someone chasing after knowledge like a finish line. Instead, I’m sketching the rough outlines of a larger map, one full of intellectual ‘here be dragons’ warnings, where the unknown isn’t a threat but an invitation. It’s a journey that began with a search for definitive answers, but now I realize the importance of remaining open to the ever-evolving nature of truth, and so I’m not turning back. My brain feels like it’s expanding into a new dimension, embracing different ways of thinking. The books I’ve encountered have not only filled my mind but also expanded its capacity to question and explore. Maybe that’s what this year of reading was about: not knowing everything, but learning how to stand in the dark and still push forward. That feels like progress. Here’s to more dragons, more questions, and more minds set on fire.